- Informe: francés

Resumen

Since gaining independence in 1960, Mali has made continuous efforts to preserve and promote the elements of the national heritage.

On the international level, Mali has ratified several Conventions, including the 2003 Convention. In implementing this Convention, Mali’s work has resulted in the inscription of six elements on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (the “Cultural space of the Yaaral and Degal” in 2008; the “Septennial re-roofing ceremony of the Kamablon, sacred house of Kangaba” in 2009; the “Manden Charter, proclaimed in Kurukan Fuga” in 2009; the “Cultural practices and expressions linked to the balafon of the Senufo communities of Mali, Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire” in 2012; multinational nomination submitted with Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire and the “Practices and knowledge linked to the Imzad of the Tuareg communities of Algeria, Mali and Niger” in 2013; multinational nomination submitted with Algeria and Niger and the “Coming forth of the masks and puppets in Markala” in 2014) and two (02) elements on the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding (the “Sanké mon, collective fishing rite of the Sanké” in 2009 and the “Secret society of the Kôrêdugaw, the rite of wisdom” in Mali in 2011).

At national level, the “Cultural space of the Yaaral and Degal” was classed as national heritage by Decree No. 08-789/P-RM of 31 December 2008; the “Sanké mon, collective fishing rite of the Sanké” by Decree No. 2011- 239 P-RM of 12 May 2011, the “Manden Charter, proclaimed in Kurukan Fuga” by Decree No. 2011- 238 P-RM of 12 May 2011, the “Septennial re-roofing ceremony of the Kamablon, sacred house of Kangaba” by Decree No. 2011- 237 P-RM of 12 May 2011, the “Secret society of the Kôrêdugaw, the rite of wisdom” by Decree No. 2011-236 P-RM of 12 May 2011 and the “Cultural practices and expressions linked to the Balafon (Bala)” by Decree No. 2012-732/P-RM of 28 December 2012. The same elements are inscribed in the national cultural heritage inventory.

Since 2005, Mali has established an indicative list of five forms of cultural expression with a view to proposing them for inscription on the List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Following the inscription of the “Manden Charter, proclaimed in Kurukan Fuga”, the “Septennial re-roofing ceremony of the Kamablon, sacred house of Kangaba”, the “Secret society of the Kôrêdugaw, the rite of wisdom” and the “Coming forth of the masks and puppets in Markala”, the Indicative List now includes the “Sigi”, a Dogon initiation ceremony that commemorates the transfer into a snake of the soul of the first dead ancestor, mass weddings at Banamba and the Dogon divination table or art.

In order to comply more closely with the inscription criteria and to ensure that the elements are regularly monitored, the capacities of the National Directorate of Cultural Heritage have been strengthened with the creation of nine (09) Regional Cultural Directorates and nine (09) Cultural Missions around the cultural heritage elements inscribed and/or classified.

At local level, a local heritage safeguarding commission has been created in each municipality, made up of administrative, municipal and customary authorities, the role of which is to inform and raise the awareness of the communities. The commission gives its opinion on all questions relating to the protection and promotion of local heritage and is responsible for organizing the communities to participate in work to restore, maintain and operate cultural infrastructures.

Despite the many efforts made, the cultural elements are not protected from threats, including the insecurity that remains after Mali’s security crisis in 2012 and inclement weather. Religious extremists have banned the populations from experiencing their traditions, social practices, rituals and festive events, let alone enjoying oral expressions and ceremonial performances. It is therefore important to persevere and be vigilant at all levels.

Resumen

The Direction Nationale du Patrimoine Culturel (DNPC, National Directorate of Cultural Heritage) is the national body charged with cultural heritage policy-making and coordination, namely the identification, safeguarding and promotion of national cultural heritage. Its capacities for safeguarding have been strengthened by the creation of Directions Régionales de la Culture (DRC, Regional Cultural Directorates) in each region and Missions Culturelles (MC, Cultural Missions) dedicated to all the inscribed and/or classified elements. At the local level, in each commune a commission for cultural heritage is created, which is made up of the administrative, community and customary authorities and leaders. It gives advice on all matters concerned with the safeguarding and promotion of local heritage and organizes community participation in the restoration, maintenance and running of cultural infrastructures.

The DNPC has undertaken training in the safeguarding and promotion of intangible cultural heritage, inventorying intangible cultural heritage and documentary photography aimed at groups and community associations engaged in safeguarding heritage and at school teachers. In addition to the DNPC, the Institut Universitaire de Développement Territorial (IUDT, University Institute for Territorial Development) is involved in providing training in the safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage.

The DNPC is also the lead institution active in documenting intangible cultural heritage, along with other institutions such as the Direction Nationale des Bibliothèques et de la Documentation (DNBD, National Directorate for Libraries and Documentation); the Institut des Sciences Humaines (ISH, Human Sciences Institute); and the National Museum of Mali, whose activities include research into and the documentation of intangible cultural heritage (collecting information on tales, divination and secret societies). The rituals, ceremonies and festivals organized by the communities that the Ministry of Culture and its regional and local offshoots help to finance also provide information that forms the basis for inventorying and which is provided to the DNPC for its evaluation. The final documentation is then validated by community representatives. There is also a dedicated research and documentation centre for the cultural space of Yaaral and Degal, which is attached to the Regional Directorate of Culture of Mopti. Each of these institutions has a guidance and reception desk in order to facilitate users’ access to the service, while providing them with information and advice, enhancing access to knowledge about cultural heritage, youth education, and promoting research.

The DNPC is charged with identifying and inventorying Mali’s cultural heritage, which it does in cooperation with the Regional Directorates of Culture and Cultural Missions. This has been built up in stages. An outline of a national cultural heritage inventory was established in 2003. A pilot inventory of intangible cultural heritage was undertaken in Koulikoro, Sikasso Segou and Gao Regions in 2007 and, from 2007 to 2010, inventories of tangible and intangible heritage were conducted in several communes or focused on specific elements. A General Inventory of National Cultural Heritage is currently underway. Sessions for training trainers and interviewers have taken place and interviews began in 2011; the preliminary results of these are being collated.

Information is collected in the communities and among producers and bearers and transmitted through the DRCs and MCs to the DNPC. The criteria used for inclusion of intangible cultural heritage elements in the inventory are that they be: characteristic of the local culture; acknowledged by communities as the hallmark of their cultural identities and factors of cultural diversity; and living, traditional elements of intangible cultural heritage that provide local people with a sense of identity and continuity. The viability of intangible cultural heritage is taken into account in the inventory form (fiche). The form used is based on that supplied by UNESCO, but with some modifications. The methodology used involves conducting library research concerning the locality and ethnic groups concerned, and then revising or updating the inventory form. In order to minimize difficulties, information and sensitization missions are conducted with the local administrative, community and customary authorities. These field trips also allow for the identification of places for study according to the criteria and local interviewers, who are then trained in the use of the inventory form.

Among the measures to ensure the recognition of, respect for and enhancement of intangible cultural heritage, the Ministry of Culture regularly provides financing (through its regional and local bodies) for rituals, ceremonies and festivals organized by communities. National Cultural Heritage Week also serves to strengthen and promote intangible cultural heritage by providing a forum for the exchange of experiences between institutions, cultural professionals, decentralized groupings, communities and civil society on current problems relating to the safeguarding and promotion of national intangible cultural heritage. Debates and quizzes on intangible cultural heritage are also held for school pupils. The DNPC also organizes radio and TV programmes on aspects of intangible cultural heritage, including its transmission, in addition to putting out promotional products and materials for use by local actors (city councils, heads of schools, village councils etc.). The government also promotes the status of intangible cultural heritage and its practitioners by proclaiming leading exponents Living Human Treasures, seven of which were proclaimed in 2008.

Education in cultural heritage provided by the DNPC to young school pupils through guided visits to sites and cultural spaces and sociocultural activities about these sites and monuments is one of the most important means for them of acquiring knowledge about and an understanding of the past, safeguarding intangible cultural heritage and strengthening their cultural identity. Building upon a workshop conducted by the École du patrimoine africain (EPA, African School of Heritage), a national network was created in Mali to advocate for integrating intangible cultural heritage elements into teaching programmes and teacher training and also to prepare an educational guide for this. These formal education efforts take on added importance because of the obstacles to traditional transmission processes and non-formal learning.

With regard to bilateral, sub-regional, regional and international cooperation, Mali, Burkina Faso and Côte d’lvoire have organized many meetings and exchanges of experience on the cultural practices and traditions related to Balafon and the cultural space of the Senufo. The resulting expert documents are shared among the institutions and made available to communities, practitioners and producers of intangible cultural heritage. Such exchanges of information and documentation also occur between the Directorates in Mali and Burkina Faso responsible for inventorying intangible cultural heritage, especially the methodology for improving inventory forms. The DNPC has also participated in various sub-regional seminars, such as: the reinforcement of intangible cultural heritage through the cultural industries (Senegal); the role of intangible cultural heritage in strengthening intercultural and civilizational dialogue (Chad); the shared heritages of North Africa and the Sahel (Morocco); and memory and policy (Kenya).

Mali reports here on three elements on the Representative List: the cultural space of the Yaaral and Degal (incorporated in 2008, after having been proclaimed a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2005); the Manden Charter, proclaimed in Kurukan Fuga (2009); and the Septennial re-roofing ceremony of the Kamablon, sacred house of Kangaba (2009). National Heritage Week (2010) was dedicated to the Malian intangible cultural heritage elements on the Representative List and included information and sensitization sessions, radio and TV programmes, debates etc. in Bamako and regional centres. The inscription of the Charter of Manden has encouraged local populations and the diaspora, researchers, culture professionals, cultural associations etc. to learn more about the element and promote it. The inscription of the re-roofing ceremony of the Kamablon has made it easier for the local population to contact the authorities and create a community contact group that aims to establish exchanges with its partners, providing information, sensitizing the public etc. In formal education, efforts are being made to intensify current activities, especially by strengthening capacities within communities; the first step will be to integrate living heritage elements related to Yaaral and Degal into educational programmes within the areas concerned. Community participation in decision-making processes for the safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage are strong in Mali and the communities also have traditional roles to play in these, based on custom. As a result, the local authorities (acting as ‘agents’ of the DNPC) directly consult and work with these traditional structures in their safeguarding activities.

Sobre elementos de la Lista de salvaguardia urgente

El sanké mon, rito de pesca colectiva en la laguna de Sanké, inscrito en 2009

- Informe: inglés|francés

- Decisión: 9.COM 5.b.4

Resumen

Traditionally, the Sanké mon collective fishing rite takes place in San in the Ségou region of Mali every second Thursday of the seventh lunar month to commemorate the founding of the town. The Sanké mon rite marks the beginning of the rainy season. It is also an expression of local culture through arts and crafts, knowledge and know-how in the fields of fisheries and water resources. It reinforces collective values of social cohesion, solidarity and peace between local communities. As mentioned in the report, at the time that safeguarding activities were initiated following its inscription in 2009, the Sanké mon element was seriously threatened by exogenous factors (climate change and natural catastrophes) and endogenous ones (conflict, anthropogenic pressures and social changes). In the meantime, in 2013, an emergency international assistance was granted to Mali to contribute to the safeguarding of its intangible cultural heritage through inventories, capacity-building and awareness-raising, with a priority given to the north and central east regions.

Effectiveness of the safeguarding activities

Safeguarding objectives are reported to included awareness-raising, capacity building of the local community to improve management of the element and training the community on the economic and socio-cultural importance of safeguarding the rite. Overall, it is stated that the main objectives have been achieved through various activities such as: fieldwork on cultural practices and expressions undertaken by local investigators and substantial data collected; radio programmes in local languages on the socio-cultural values of the Sanké mon; photographic exhibitions of previous enactments of the ritual; information and awareness-raising meetings on the conservation, good management and annual organization of the Sanké mon; capacity-building training sessions for the cultural communities on the management of the element and its related socio-cultural resources. As explained by Mali in its report, the results obtained have been shared through monitoring and evaluation workshops and are deemed to be satisfactory by the stakeholders involved in safeguarding and transmission of the element.

Community participation

The involvement of the community at all stages of safeguarding is reported as notable and their continued capacity to manage the process is being developed. The safeguarding measures were achieved on the basis of a holistic and participatory approach that involved all key actors, notably the communities, groups and important individuals of the San bearer community. The report notes that the local inhabitants of San are strongly attached to the rite, which they consider as essential to their identity and its continuance as a sacred obligation, leading to their mobilization and participation in the traditional fishing ceremonies despite challenging circumstances. The use of local investigators for collecting has been an important aspect of their participation, and the communities themselves have contributed to improving and validating the results of the field investigations. Cultural associations and socio-professional groups of a cultural character are also involved in the implementation of the activities. According to the State Party, community participation in all meetings, studies and exchanges maintains the traditional channels of transmission by the bearer communities. This also allows for better mobilization of local actors and improved safeguarding and management of the element. As a consequence, it is reported that there are encouraging signs of sustainable safeguarding and management of the element.

Viability and current risks

Civil strife in the regions of North Mali has strongly influenced the intangible heritage of the communities and the last two performances of the Sanké mon element have been disturbed. In addition, it is noted that the food routes in the water have been obstructed, the city of San has experienced rapid urbanization and youth disinterest, and there has been lack of water in the pond due to low rainfall. Some elements have been lost (e.g. men disguised as women, donkey races), although in the report it is mentioned that it is not clear what the impact has been. While some of the risks remain, according to Mali safeguarding measures taken have greatly contributed to mitigate them. The pond has been refurnished in water and fish for the rite, measures have been taken to protect the location around the pond and work is being done by parents and elders to transmit the rite to future generations and raise their interest. Moreover, the element is protected by official legislative acts and customary law, as mentioned in the report.

Sociedad secreta de los Kôrêdugaw, el rito de la sabiduría en Mali, inscrito en 2011

Resumen

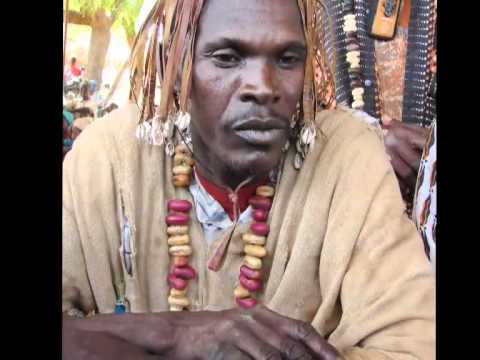

The ‘Secret Society of the Kôrêdugaw, the rite of wisdom in Mali’ is an initiation rite dedicated to the quest for wisdom that encompasses an aspiration towards immortality of the soul through the spiritual guidance of community life. Initiates (the Kôrêdugaw) provoke laughter with behaviour characterized by caustic humour, but also possess great intelligence and wisdom. The Kôrêdugaw play the role of social mediators (e.g. conducting reconciliation of inter-and intra-community conflicts), educate children, help to cure illnesses through traditional medicine, attend various ceremonies (marriages, baptisms, funerals and official receptions), and try to invoke heavy rains and abundant harvests. They symbolize generosity, tolerance, and mastery of knowledge, embodying the rules of conduct that they advocate for others. The secret society of Kôrêdugaw is an essential part of the cultural identity of the Bambara, Malinké, Senoufo and Samogo peoples.

Effectiveness of the safeguarding plan. Under the responsibility of the Cultural Heritage Directorate (DNPC) from the Ministry of Culture and with the active participation of the bearer communities, communal and customary authorities, and the Kôrêdugaw associations, the following safeguarding measures have been undertaken: (i) establishment of Kôrêdugaw associations throughout the country; (ii) promotion of the element through conferences, broadcasting radio programmes, exhibitions and meetings between Kôrêdugaw associations and various authorities in different regions; (iii) an educational programme targeting young people in schools; (iv) capacity building of Kôrêdugaw associations on fundraising and safeguarding needs’ identification; and (v) documentation by inventorying, conducting field studies, and making audiovisual recordings and brochures.

According to the report, the safeguarding measures have greatly contributed to revitalizing the element. At the core of the safeguarding process, the bearers (through the Kôrêdugaw associations) have strengthened the communities’ sense of ownership of the element and greatly mobilized the populations around the Society. The communities have become more aware of the potential negative impacts of the degradation of the customs and have responded by organizing festivals and informing the broader public about the importance of the element. Women and young people, in particular have shown a strong interest in learning and transmitting their parents’ traditional practices and knowledge. Among the activities, the use of radio broadcasts in local languages has allowed for widespread dissemination of the intended message while the distribution of brochures has informed people of threats to the element. The educational programme organized in schools has taught young people about the history and values of the Society as a guide to behaviour. Festivals on the Society have achieved popular mobilization and have now been included in economic development budgets of the local communes. According to the report, lack of financial resources and logistical support has constituted the only obstacle to the implementation of all planned activities.

Community participation. The communities of Koulikoro, Ségou and Sikasso regions actively participated in the preparation and implementation of the safeguarding activities through their representatives, associations, and initiated and resource persons. In particular, the numerous Kôrêdugaw associations played a central role and greatly contributed to making the safeguarding approach inclusive. They met with the administrative, political and customary authorities in each region and also organized working sessions with village councils, notables and local resource persons for this purpose. In addition, the parental associations of school children mobilized school-age pupils. The report has been established with the contribution of local authorities and the Kôrêdugaw associations who help to identify community representatives in the Koulikoro, Ségou and Sikasso regions to gather information through field investigation teams.

Viability and current risks. The viability of the element now relies on the large number of associations protecting and promoting the Society. As mentioned in the report, today it is through these associations that the initiation’s rites are organized in all bearer communities. The practitioners come from all social and professional backgrounds and ethnic groups and entry to the Society is open to all, which is a further aspect of its viability. In addition, non members also participate in the element, such as young people and women who contribute to the Kôrêdugaw gatherings and festivals. Kôrêdugaw associations’ membership fees help to fund the safeguarding activities and thus contribute to the sustainability of the element.